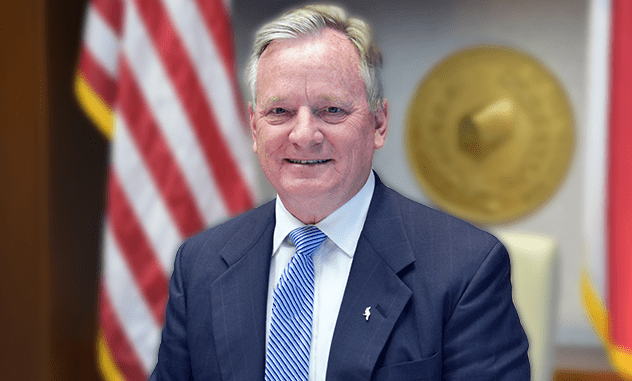

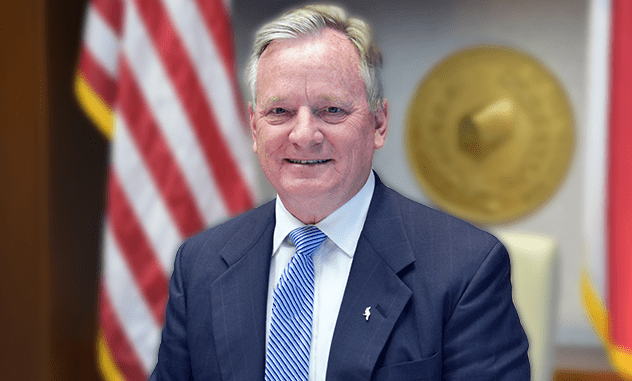

RALEIGH — During a Feb. 15 press conference, State Treasurer Dale Folwell unveiled a report detailing the high pay of executives of nonprofit hospitals operating in the state.

“You’ve heard me say before that what we’re dealing with in the health care industry is like an onion,” said Folwell. “The more we peel it, the more we cry. And the situation is getting far worse.”

“What you’re going to see from this report – if you can even imagine the situation getting worse – we are seeing a massive transfer of wealth from workers to hospital executives,” Folwell said. He added the healthcare executives were incented to raise profits but apparently not raise care quality or lower costs.

The report, titled “Nonprofit Hospital Executive Pay,” gives an overview of how the pay for top officials in charge of nonprofit health facilities doubled their paychecks in less than five years.

According to the report North Carolina hospitals paid $1.75 billion to their top executives from 2010 to 2021. Around 20% of that pay went to top executives, translating to a collective $308.8 million over 12 years.

Examples given by Folwell and his staff included Atrium CEO Gene Woods collecting $9.8 million, a 473% pay increase, in just a six-year period leading up to 2021. Similarly, Mission Health CEO Ronald Paulus saw his compensation rise 726% in less than a decade.

Hospital executive compensation during the pandemic stayed on the rise despite taking $1.5 billion in COVID relief funds. The report says that of the 175 executives across the eight healthcare systems, only 35 took a pay deduction that was not triggered by a departure during 2020.

Other 2020 pandemic-related findings included an average CEO compensation of $3.4 million with the top 40 hospital executives collecting a total of $77.2 million in 2020. The report equates the over $77 million as “enough to pay the average salaries of 1,412 teachers.”

The report describes medical debt incurred by patients during the pandemic and says that some nonprofit hospitals in the state “billed more than $149 million to poor patients who should have received charity care,” and that the state’s largest nonprofit hospitals “encouraged thousands of North Carolinians to sign up for “medical credit cards” that can charge up to 18% interest,” the report states.

Folwell pointed out that the report is incomplete because it does not include outside compensation paid to CEOs and top executives. An example given by the treasurer is UNC Health’s CEO William Roper who was paid $5.5 million as a result of sitting on boards of outside organizations that did business with the state.

Another factor impeding the report’s estimation of executive compensation is a lack of ability to view hospital tax filings. Folwell said loopholes in the current law governing those filings meant that over three in ten of the nonprofit hospitals were able to keep their filings out of the public view.

Suggested transparency remedies asking lawmakers to “require publicly owned hospitals to abide by the same transparency standards as other nonprofit hospitals that publish tax filings.” In the same vein, the report suggests “policy makers should reconsider allowing hospitals to conceal the structure of their top executives’ compensation in contracts.”

Folwell also said that the report did not include some of the latest data his office had just received via public records requests submitted to UNC Health.

In his closing, Folwell recalled his earlier remarks about the NC Chamber’s president asking him to stop calling the healthcare system a “cartel.”

“I want to tell everybody at the same time, I will stop using the word cartel when they stop acting like one,” Folwell said.

Various experts joined Folwell for the press event, which was streamed on his department’s Facebook page.

Those joining the treasurer included Dr. Vivian Ho, James A. Baker III Institute Chair in Health Economics at Rice University; Dr. Hossein Zare, professor and assistant scientist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; and Dr. Ge Bai, professor of health policy and management at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and professor of accounting at the Carey Business School.

Support for the report also came from Ardis Watkins, executive director of the State Employees Association of North Carolina.

Ho called the report “a wake-up call to anyone who sits on the board of a nonprofit hospital.”

Zare remarked that while nonprofit hospitals are required to justify community benefits spending at the tax level, it was hard to tell what these entities were really doing.

“Lack of transparency on definitions and spending creates a wide variation across nonprofit hospitals in the amount of tax benefit and charity care/community benefits,” Zare said. “A new standard is needed.”

A set of peer-reviewed reports commissioned by Folwell showed nonprofit hospitals received over $1.8 billion in tax breaks in 2020, but the majority of hospitals didn’t justify their exemptions through an equivalent level of charity care.

A statement from the North Carolina Hospital Association called the report a “distraction” from what they called a secretive selection process for the new third-party administrator for the State Health Plan and called questioning executives’ commitment to improve the health of patients and communities egregious.

The full report can be accessed on the N.C. State Health Plan website:

https://www.shpnc.org/what-the-health/hospital-executive-pay-nc