Willy T. Ribbs knew what he wanted when Adam Carolla approached him about doing a documentary on the former pro racer’s life.

Carolla, a comedian, radio personality and podcast host, wanted to tell the story of Ribbs, the first African American to race in the Indy 500, the first to drive a Formula One car and one of a handful to drive in a NASCAR Cup Series race.

Ribbs agreed to let Carolla direct the documentary, but he had his conditions.

“One of the stipulations was that if we’re gonna do this, we’re not gonna pull any punches,” Ribbs said. “We’re not gonna gloss it over. They’re gonna get butt hurt. Right? Sometimes that truth hurts. It’s like taking strong medicine that your grandma used to give you. It ain’t gonna feel good in the beginning but you’re gonna like it later.”

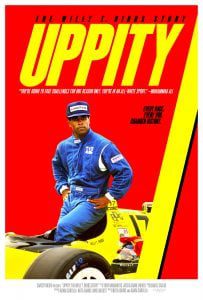

The result, “Uppity: The Willy T. Ribbs Story,” delivered.

“I was prepared to be disappointed,” Ribbs said.

He wasn’t. “Uppity” tells the story of Ribbs’ start in auto racing, when he took the money he’d saved for college and spent it for a spot in England’s Formula Ford racing circuit. After winning the championship in his first year, he returned to the U.S. only to see his career stall due to lack of interest from sponsors — critical for someone starting out in the uber-expensive world of auto racing — and hostility from other drivers.

“I wasn’t called uppity when I was in England,” he said. “They didn’t know the word there. When I came back to America, I became uppity.”

The reception took Ribbs somewhat by surprise.

“I went in with the — I don’t want to say naïve thought,” he said, “but my feeling was if I liked racing and I liked racing drivers, they had to be good people. That was my thought. I mean, they couldn’t be bad people, if I liked what they were doing and I was trying to do what they were doing, then I would automatically be one of them. Well, no, I wasn’t.”

Ribbs responded not by turning the other cheek but by battling the forces he saw massing against him head-on. He fought other drivers, feuded with teammates and clashed with team owners as he sought a spot in a world that hadn’t seen many people who looked like him and showed no signs of wanting to see any again soon.

“You will see three more black presidents before you see a black NASCAR champion,” Ribbs told North State Journal. “Do you hear what I’m saying? And they could fix that today. They could get in a room and fix that in minutes. But they won’t.”

Clearly, “The Jackie Robinson Story,” this is not. Ribbs met with Muhammad Ali while racing in England and learned from the former heavyweight champion how to make his mark as a black in American sport. It’s one of the reasons Ribbs eventually adopted his trademark celebration in victory lane, where he would climb atop his car and do the Ali shuffle on the roof.

Despite countless pleas to dial things back and play the game, Ribbs refused, instead doing what he thought was right and calling out racism and double standards where he saw them.

“Dialing it back was a way to sweep you under the carpet,” Ribbs said. “Stay quiet, and you’ll disappear in the sunset. That’s the oldest trick in the book. No, no. We’re not dialing anything back. As a matter of fact, we’re gonna ratchet it up a little bit and see how you like it. That’s how I was brought up. There’s right and wrong. There’s no gray area. And when you’re right, you don’t turn the other cheek.”

As expected, Ribbs was not accepted warmly by the majority of racing fans. His NASCAR debut, scheduled at Charlotte Motor Speedway, had to be called off due to death threats.

“A lot of people ask me how did you feel about all that? Were you intimidated by death threats and the N-word and all that? I say, ‘Oh, no. That was fun.’ … You know what? It was sort of a turn-on, actually. I won’t tell you what kind of a turn-on.”

Later, when he raced at North Wilkesboro, he was greeted by boos thundering down from the capacity crowd.

“I started laughing,” he said. “And they saw me laughing and booed even more. I expected to hear some boos, but not the whole stadium, right? Dale Earnhardt Sr. looked at me and he sort of shook his head and put his head down. I could tell he was embarrassed by it. And I looked at him and I started laughing and said, ‘Wow! They know me!’ That was awesome, man.”

Throughout his career, Ribbs showed that, when he had equal equipment, he could drive with the best of them — and win more often than not. The trouble was paying for the engines, tires and other equipment needed to compete at the highest level.

He received support from luminaries such as Paul Newman, Don King and Bill Cosby. At the time, Cosby had the top-rated show in America and sponsorship deals with All-American companies such as Coke and Jell-O. Still, Ribbs couldn’t get the corporate money to help keep his team afloat.

He received support from luminaries such as Paul Newman, Don King and Bill Cosby. At the time, Cosby had the top-rated show in America and sponsorship deals with All-American companies such as Coke and Jell-O. Still, Ribbs couldn’t get the corporate money to help keep his team afloat.

“The sponsors were not nice to me,” he said. “They didn’t call me the N-word. They just didn’t support me.”

Still, on a shoestring budget and a hand-me-down car, Ribbs was able to qualify for the Indianapolis 500, breaking the race’s color barrier in 1991. Two years later, he became the first African American to finish the race.

Only one other black driver has followed him. It would be another 13 years after North Wilkesboro before another African American started a NASCAR Cup Series race.

“When I tested a Formula One car, that was the year Lewis Hamilton was born,” he said. “To this day, only two African Americans have driven a Formula One car — Willy T. Ribbs and Lewis Hamilton.”

Ribbs broke barriers, but he’s watched as followers struggled to come through behind him. He blames it on the people controlling the money.

“African Americans in this country spend billions and billions and billions on Chevrolet and General Motors and Ford and beverages like Coca-Cola, all the advertisers that are in the sport of auto racing. … To this very day, today, in 2020, that market is still not tapped by the auto racing industry. Formula One has got it, but Indy Car and NASCAR and sports car racing, they don’t have it. And I don’t know, maybe they don’t’ want it. Golf got it. Auto racing — they haven’t caught on yet.”