LOS ANGELES — A late-hour attempt to extend the life of California’s last nuclear power plant has run into a predicament that will be difficult to resolve: a shortage of time.

A state analysis Monday predicted it will take federal regulators until late 2026 to act on an application to extend the operating run of the Diablo Canyon nuclear power plant. The problem is that the plant is scheduled to shut down permanently by mid-2025.

The future of the state’s remaining reactors could hinge on operator Pacific Gas & Electric’s request to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission for an unusual exemption that would allow the decades-old reactors to continue making electricity while the NRC reviews the application – not yet filed — to extend its licenses for as much as two decades.

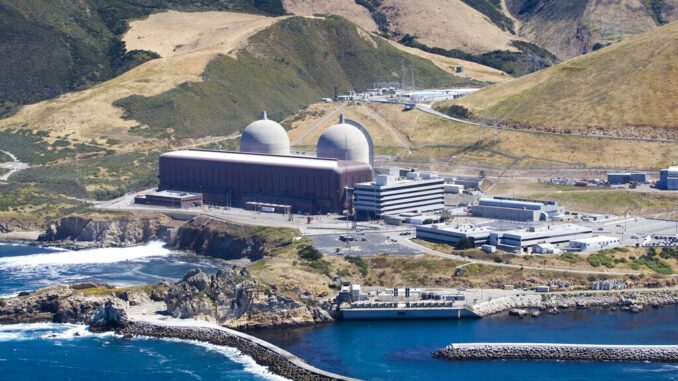

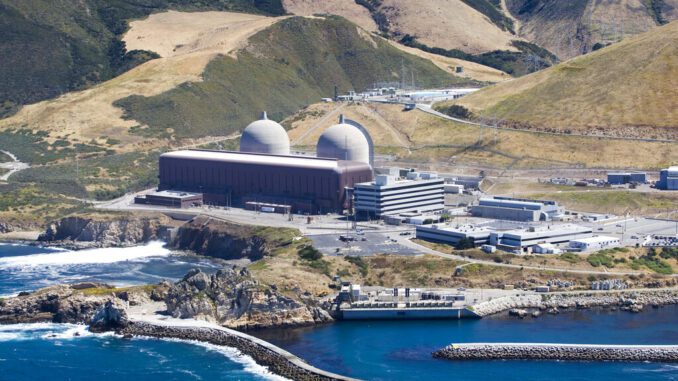

One reactor is scheduled to close in November 2024, and its twin in August 2025. The plant is located on a seaside bluff, midway between Los Angeles and San Francisco.

On Monday, anti-nuclear activists and national environmental groups urged the federal agency to reject the request, saying in a petition that the exemption would amount to a dangerous, unprecedented shortcut that would expose the public to safety risks from reactors that began operating in the mid-1980s.

“There is absolutely no precedent for the exemption requested by PG&E. The NRC has never allowed a reactor to operate past its license expiration dates without thoroughly assessing the safety and environmental risks,” Diane Curran, an attorney for the anti-nuclear advocacy group Mothers for Peace, said in a statement.

The dispute over the potential exemption is the latest battlefront in a long-running fight over the safety of the reactors. Construction of the Diablo Canyon plant began in the 1960s and critics say potential shaking from nearby earthquake faults, not recognized when the design was first approved, could damage equipment and release radiation. One nearby fault was not discovered until 2008. PG&E has long said the plant is seismically safe; federal regulators have agreed.

Democratic Gov. Gavin Newsom — who once supported closing the plant — did a turnaround last year and argued it needed to keep running beyond the scheduled closure to ward off possible blackouts as the state transitions to solar and other renewable sources. At his urging, the Legislature dissolved a complex 2016 agreement among environmentalists, plant worker unions and the utility to close the plant by 2025, opening a pathway to keep it running longer. The utility said it changed direction given the energy policies adopted by the state.

PG&E officials have said they are eager for certainty about the plant’s future because of the difficulty of reversing course on a plant that was headed for permanent retirement, but now needs to prepare for a potentially longer lifespan.

In October, the utility asked the NRC to resume consideration of an application initially submitted in 2009 to extend the plant’s life, which later was withdrawn after PG&E in 2016 announced plans to shutter the reactors when the licenses expired.

But the idea of going back in time to resume consideration of the previous filing was rejected by the agency, leaving PG&E with the time-consuming task of submitting a new application that it expects to file by the end of the year.

Reviewing a request for an extended license typically takes two years or more. Without extended licenses, that means one reactor, or both, might have to close while the NRC reviews the applications.

That led to a separate request: PG&E wants the NRC to allow the plant to continue running beyond its current, authorized term while the federal agency considers the license extensions. That ruling is not expected until next month.

Typically, if a nuclear plant files for a license extension at least five years before the expiration of the existing license, the existing license remains in effect until the NRC’s application review is complete, even if it technically passes the expiration date. But PG&E would not meet the usual five-year benchmark.

In documents submitted to the NRC, the company said the change it’s seeking “will not present an undue risk to the public health and safety.”

Without the exemption, the NRC would have less than a year to conduct the license-extension review — far less time than is typical — before the current license expires and the plant would be required to close.

The environmental groups said conducting a truncated review in just months “would be difficult if not impossible” and raise safety risks for a plant that until recently was headed for closure.

Completion of the NRC review, before a longer run is permitted, is needed “to assure that continued operation of the reactors will be safe,” they wrote.